How common is physiological jaundice in term infants?

Neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia, often referred to as Jaundice is the most common condition requiring medical attention, hospitalisation and treatment in the newborn period (Alkalay et al 2010) and is a common reason for admission to the neonatal unit.

With an average admission length of stay of 24 hours for a newborn requiring phototherapy treatment, this is a big cost for healthcare providers and private health insurance companies. If there is anything we can do to try and reduce the duration of treatment and stay in a special care nursery then this has to be of benefit to the infant and family.

Approximately 60% of term infants and 80% of preterm infants will show signs of jaundice within the first 7 days of life. In 2020, 3.6% of all babies born in Queensland had jaundice levels requiring phototherapy treatment (Qld Clinical Guideline: Neonatal Jaundice 2022).

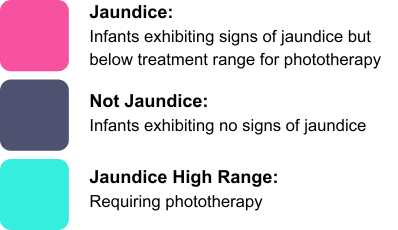

.png)

What causes physiological jaundice?

Hyperbilirubinaemia occurs when there is a disparity between the production, conjugation and excretion of bilirubin. The natural degeneration of red blood cells and haemoglobin causes high levels of unconjugated bilirubin to accumulate in the blood. The liver of a newborn infant is very immature at birth and does not function as effectively as an adult, the processing of toxins and waste products is much slower, resulting in a higher probability of jaundice.

Unconjugated bilirubin binds to albumin and from there it is transported to the liver where it is converted to conjugated bilirubin. Once it becomes a water soluble state it can then be easily processed and eliminated by the liver and excreted through urine and faeces.

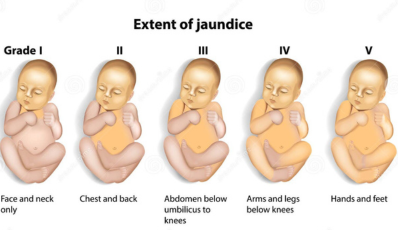

Physiological jaundice normally begins to manifest after 24 hours of age and is often very transient in nature. The infant usually presents with a yellow colouring of the skin and sclera of the eyes. The below diagram shows how visual jaundice is graded from one to five in the hospital setting, the higher the grade the higher the serum bilirubin level is likely to be. Jaundice at high levels is extremely dangerous and can cause kernicterus leading to brain damage and in severe cases, death (Kaplan et al 2011).

ID 150028261 © Viktoriia Kasyanyuk | Dreamstime.com

How are jaundice levels monitored?

Transcutaneous, non -invasive measurements can be taken using a bilimeter. This can be used on infants from 35 weeks gestation. If the level is >250micromol/litre this will need to be confirmed with a Serum Blirubin level (SBR) for accuracy prior to determining treatment. This requires the infant to undergo a heal prick blood sample test.

An SBR is the benchmark in the hospital setting and the result needs to be plotted on to a nomogram. If the level is above the treatment zone, this reflects the need for phototherapy. The level will determine the number of lights that the infant will need to treat the jaundice. These graphs are available in gestational ranges to include the preterm population.

.png)

Qld Clinical Guideline: Neonatal Jaundice (Dec 2022)

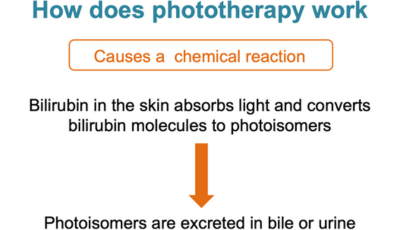

What is phototherapy?

Phototherapy has been used in the treatment of neonatal jaundice for almost half a decade. It is a blue spectrum light source delivered at a range of 460nm, It can be applied both above and/or below the infant and through penetration of the skin, converts bilirubin to water soluble form so that it can be excreted via the liver without conjugation occurring.

The basic concept of phototherapy is to change the structure of bilirubin, converting it into an excretable form.

Has infant massage been shown to assist in lowering bilirubin levels alongside phototherapy?

A study by Chen et al (2011) reported that full term infants who received massage therapy, alongside phototherapy, had significantly lower SBR levels than those infants who did not receive massage over the same time period.

This result is also supported in a further study carried out by Santosa et al in 2022, their data showed a significant drop in SBR levels of 12mg/dl for those infants receiving massage twice a day for 15 minutes over 4 days.

What physiological effects can massage have in lowering bilirubin levels?

The massage sequence performed on infants targets the abdomen stimulating intestinal movement and peristalsis, which has been proven to increase the frequency of bowel movements in the target groups studied.

Massage therapy is emerging as a potential intervention to reduce the need for phototherapy and lower SBR levels as research is showing that it increases the excretion of meconium through the bowel which successively reduces the enterohepatic circulation of bilirubin, thereby leading to a faster excretion (Doğan E et al 2023).

What part does the parasympathetic nervous system play in relation to jaundice and infant massage?

The vagal nerves carry signals between your brain, heart and digestive system. These nerves form a key part of your parasympathetic nervous system.

Massage stimulates the vagus nerves, which has been proven to increase the frequency of bowel movements and diminish the circulation of bilirubin by producing increased intestinal peristalsis in the infant.

Lestari et al (2021) suggested that by stimulating the vagus nerve, it will in response increase the production of food absorbing hormones. This will enable the infant to develop an improved tolerance of milk and will encourage them to feed regularly and also empty their bowels regularly, further assisting with the removal of bilirubin from their system.

Chen et al (2011) also previously supported the findings of Lestari et al (2021) suggesting that stimulation of the vagus nerve can increase the secretion of gastric and pancreatic juices therefore increasing the amount of milk intake and overall improvement of digestive function. The suggestion would be that increased frequency of defecation vastly decreases bilirubin reuptake secreted in the intestines.

.png)

How is the massage performed?

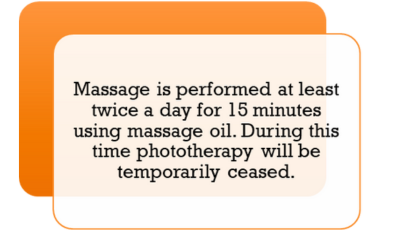

Literature would suggest that the massage will need to be performed two to three times per day with a pause of phototherapy for ten to fifteen minutes for the duration of massage. The massage technique followed is that of Field et al (1986)

Bagshaw and Fox in 2005 described Infant Massage as a non-invasive therapeutic technique. It is inexpensive and does not require any high-level skilled personnel, if parents are able to be involved. It can also be carried out alongside traditional medical treatments potentially resulting in a shorter stay in hospital.

Massage is performed using smooth strokes starting from the legs to the abdomen, hands and back, but can also start from the face, moving on then to the chest, abdomen (according to the direction of the colon) and lower body and the back using a suitable organic massage oil.

The massage sequence follows an Indian massage technique which is known for drawing toxins away from the body. In subcutaneous tissue the process of massage therapy can increase the flow of blood, lymph and tissue fluids, which accelerates the collection and excretion of waste products such as bilirubin. (Chen 2011)

A patch test with oil would be required in advance to ensure that the infant does not react adversely to the oil. This process of steps has been replicated in over seven studies.

Who would carry out the massage?

Parents can be taught by professionals who are IMIS Certified Infant Massage Instructors or Paediatric Massage Consultants.

Health professionals can undertake training to allow them to perform massage on hospitalised infants if parents cannot or do not wish to be involved in the massage.

Babaei et al (2018) carried out a study involving massage administered by neonatal nurses in a neonatal intensive care unit in Iran, nurses were involved as they carried out one episode of massage during a nightshift when parents and carers were often not around. The Field massage technique was taught and followed by all staff in the study.

Infant massage is used regularly in many African and Asian countries from birth as part of routine newborn care, but has not yet been formally adopted in Australia or Europe.

Why use oil and is it safe alongside phototherapy?

Topical oil application is recommended for improving skin barrier function. Church et al (2016) and Kaplan et al (2011) suggest that oil provides an overall improvement in the condition of skin, providing moisture, antimicrobial protection and its use reduces the chance of skin injury from any friction involved in the massage process.

Agarwal et al (2000) showed that infants massaged with sesame oil achieved better overall growth and improvement of blood flow than infants massaged with other oils. Sesame oil contains up to 40% linoleic acid which is easily absorbed.

Given that phototherapy is ceased for the duration of the massage, the oil will have been absorbed into the skin prior to recommencing phototherapy with little disruption to the infant as they will continue their phototherapy treatment in just a nappy.

What benefits could parents receive through providing infant massage to their infant receiving phototherapy?

When the infant is receiving phototherapy they are often in an isolette with eye protective covers in situ which means that for the most part the parents are not able to continue that special bonding and touch with their baby. This often leads to feelings of disempowerment.

If the parents are actively encouraged and supported to carry out the massage at intervals when there is a pause in phototherapy, they are able to reconnect with their baby using a positive touch. A study by Lunnen et al (2005) showed that carers felt more confident and were less stressed and felt a closer bond with their baby after learning and performing infant massage on their baby. This supports a family centred care approach which is imperative in the special care nursery.

Why don’t we introduce infant massage to all newborn infants to reduce the risk of hyperbilirubinaemia?

This is something that IMIS recommends should be used for all newborn infants as a preventative treatment. It is a skill that can be taught to all new or prospective parents so that they can perform infant massage on their babies to increase gut motility and speed up the all-important early passage of meconium. It can be used daily as part of a newborn care regime to potentially prevent high levels of jaundice.

Given the figures representing 60% of all newborns developing jaundice within the first week of life, this is a low risk, cost effective means of reducing the probability of an infant requiring phototherapy.

Classes could be held in hospitals alongside ante-natal classes to teach parents infant massage so that they have the skills to perform massage immediately after birth as part of newborn routine care.

What further research needs to be done?

The goal of further research would be to contribute valuable and useful insights into the development of family centred care, promoting a more comprehensive understanding of the benefits of infant massage in conjunction with standard medical interventions. More studies in Australia and Europe may help the acceptance of infant massage as a therapy adjunct within the medical world.

Are there any limitations to current research?

Currently, the effect of massage on neonatal growth and development is well established and well accepted. But there is no general consensus on the effect of infant massage on neonatal jaundice as it is still seen primarily as a medical condition requiring a medical intervention. Based on the latest meta-analysis carried out by Zhang et al in 2018, massage therapy has been shown to significantly reduce SBR levels.

Current research findings however have come from Asia, Iran and the United States. There is limited research in Europe and Australia into this field.

Ethical considerations also do not allow research into the use of massage alone as a treatment for high range physiological jaundice to enable us to see whether massage alone greatly reduces SBR levels without the use of phototherapy as a medical intervention.

Conclusions and Recommendations:

It would be beneficial to trial a study recording transcutaneous bilirubin levels on infants with mild jaundice not requiring phototherapy to see if massage alone decreased the levels recorded on a daily basis in the healthy term newborn.

More studies are needed into the cohort of preterm infants in relation to phototherapy and infant massage as they are often too physiologically or developmentally unstable to receive the handling required.

Infant massage could potentially benefit both the physiological and overall general health of the newborn. Vnankani (2016) and Vincent (2011) discuss the importance of touch being one of the first senses to develop and that parent-infant touch provides endless benefits including regulation of heartbeat and temperature, as well as protection from infection and bonding.

This is a great way of allowing the bonding to continue in the special care nursery whilst also potentially assisting to provide a shorter admission. The massage is certainly of no detriment to the baby. It is a safe and economical adjunct to medical interventions. Therefore, IMIS suggests the use of infant massage in the stable term infant receiving phototherapy for physiological hyperbilirubinaemia in this special care nursery should be actively encouraged.

References:

Alkalay, A.L., Bresee, C.J., and Simmons, C.F. (2010) ‘Decreased neonatal jaundice readmission rate after implementing hyperbilirubinaemia guidelines and universal screening for bilirubin’, Clinical Pediatrics, 49 (9), pp. 830-833.

Agarwal, K., Gupta, A., Pushkarna, R., Bhargava, S., Faridi, M. and Prabhu, M. (2000) Effects of Massage & Use of Oil on Growth, Blood Flow & Sleep Pattern in Infants. The Indian Journal of Medical Research, 112, 212-217.

Babaei, H. and Vakiliamini, M. (2018) ‘Effect of massage therapy on transcutaneous bilirubin levels in healthy term neonates; randomized controlled clinical trial’, Iranian Journal of Neonatology, 9 (4), pp. 41-46.

Bagshaw, J. and Fox, I. (2005) Baby massage for dummies: the wonderful world of massage. Wiley publishing, pp. 7-17.

Chen, J., Sadakata, M., Ishida, M., Sekizuka, N., and Sayama, M. (2011) ‘Baby massage ameliorates neonatal jaundice in full term newborn infants’, Tohoku journal of Experimental Medicine, 223 (2), pp. 97-102.

Church, P., Cavanagh, A., and Shah, V. (2016) ‘Academic challenges for the preterm infant: parent and educator perspectives’, Pediatric Health Child Journals, 21 (5), pp. 274-277.

Doğan E, Kaya HD, Günaydin S. The effect of massage on the bilirubin level in term infants receiving phototherapy. Explore (NY). 2023 Mar-Apr;19(2):209-213. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2022.05.001. Epub 2022 May 27. PMID: 35660270.

Field, T.M., Schanberg, S.M., and Scafidi, F. (1986) ‘Tactile/kinesthetic stimulation effects on preterm neonates’, Pediatrics, 77 (5), pp. 654-658.

Gandhi, N. (2017) ‘ Massage child oil’ Mom junction, Nov 10.

Kaplan, M., Bromiker, R., and Hammerman, C. (2011), ‘Severe hyperbilirubinaemia: are there still problems in the third millennium?’, Neonatology, 100 (4), pp. 354-362.

Lestari, K.P., Nurbadina, F.R., and Jauhar. M. (2021) ‘ The effectiveness of baby massage in increasing infant’s body weight’, Journal of Public Health Research, 10.

Lunnen, K.Y., Clayton, K., Stokes, A., Kennedy, J., and Monor, J. (2005), ‘Outcomes of home based massage intervention for high risk infants and their families’, Pediatric Physical Therapy, 17, pp. 95.

Queensland Clinical Guidelines: Neonatal Jaundice (2022). DOC – MN22.7 – V9-R27, www.health.qld.gov.au/qcg

Viewed 22/05/2024.

Roy, C. (2017), ‘Massage for children’, Mother for life, March 6.

Santoso, S.E.S., Karuniawati, B., and Farziandari, E.N. (2022), ‘The effect of Field massage on bilirubin levels in neonates with hyperbilirubinaemia’, The International Virtual Conference on Nursing, Volume 2022.

Vincent, S. (2011), ‘Skin to skin contact part two – the evidence’, The Practicing Midwife, 14, pp. 40-44.

Vnankani, B. (2016), ‘Best massage oil for your baby’, Baby Center, India Medical Advisory Board, August 10.

Zhang, M., Wang, L., and Tang, J. (2019), ‘The influence of massage on neonatal hyperbilirubinaemia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials’, The Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 223 (2), pp. 97-102.